A Powerful Driver for a Solution to Plastic Waste

Litter of plastic is probably the most visible aspect of the production of such high volumes of plastic. Many plastics float in water and many items blow around in the wind.

While litter itself is a human caused problem, there are many factors that contribute to our overwhelming litter problem.

- It has little perceived residual value after use

- Products have no other use than the one single use they were designed for

- The products are cheap to manufacture

- It is hard not to buy plastic items or items wrapped in plastic these days

On this page are just a few examples:

- Plastic Bottles

- Plastic Bags

- Plastic Waste and Wildlife

- The Great Pacific Garbage Patch

- Plastic (resin) Pellets

Plastic Bottles

Plastic drink bottles are one of the largest plastic litter issues. Relative to drinking straws, and grocery store plastic bags, bottles are quite large and they do not readily compact down. They stand out from tens of meters away. This makes them a particularly unsightly item to be seen on the side of the road, in water ways and on beaches. During the 2008 Keep America Beautiful Great American Cleanup, volunteers recovered and recycled 189,000,000 PET (plastic) bottles that littered highways, waterways and parks. (Yes, that’s 189 million!)

In summer, after a rain storm where the storm water drains get flushed from cities into rivers, the amount of

|

plastic bottles that comes out is truly amazing. Some simple estimates can show why. Consider a big city of 3 million people. If one person in 1000 buys a drink bottle and drops it as litter a week, that makes for 3000 plastic bottles lying around as litter or washing down a waterway every week.

Plastic Water Bottles – One of the Great Cons

Plastic water bottles are items which warrant particular attention. Bottled water has been described as “one of the greatest cons of the 20th century” and as “marketing’s answer to the emperor’s new clothes”.

Roughly 200 billion water bottles are produced globally each year. The USA alone uses 2 million every 5 minutes. This plastic, which is worth multi billion dollars, usually ends up in our landfills to remain for many hundreds of years. In the United States, plastic utilized to create bottles uses an estimated 15 million barrels of oil annually. About 25 percent of bottled water is just tap water that has been packaged by major companies. Considering that tap water is almost free, consumers have been duped into paying water bottle companies and distributors large mark-ups. At the 2011 Australian Tennis Open one company was charging $8.40 for a litre (¼ of a gallon)of water. The city supplies water for $0.0015 per litre. That is a cost differential of 5600 times. In 1976, the average American consumed 1.6 gallons of bottled water. In 2009, that number jumped to 21 gallons. Why is this? In large part this has been achieved due to the clever marketing of water bottle companies convincing us that bottled water is somehow better than highly regulated tap water. In some cases this is true, but ‘manufactured demand’ comes from manufacturers trying to increase their sales at the expense of making products that they know a certain percentage of will end up as litter in the environment.

Other videos of interest on the great con of bottled water include:

The plastic bottle industry is creating a major environmental problem which is unprecedented in public litter problems, except for possibly the plastic bag. Some organizations have come to understand what problems plastic drink bottles are really causing. The town of Bundanoon in New South Wales, Australia has banned plastic water bottles and installed more chilled water fountains for its citizens. The University of Canberra in Australian Capital Territory, Australia has also banned bottled water from its campus. Two whole provinces in Canada have banned water bottles in favour of more environmentally friendly water supplies.

A Bottle Refund Scheme

A bottle refund scheme is whereby people can cash their bottles in for a cash refund. Such a scheme has been in operation in the state of South Australia since 1977. There the bottle recycle rate is a high 80% and there is a noticeable lack of bottle litter on the highways and in parks. On average in Australia the bottle recycle rate is only 28%, strongly indicating that even a small refund of $0.10 can make a significant difference to attitudes towards litter. There are other benefits to a refund scheme as well.

- Due to their bulk, drink containers compromise about 30% of total landfill litter. Reducing bottles from the litter stream saves on valuable landfill space.

- Reducing the number of drink bottles from household waste reduces the local council’s pick up and disposal cost of trash. These savings can be invested in other ways back into the community.

- Many consumers donate their bottles to community groups such as The Scouts or sports organisations. The Scouts in South Australia raise $9 million a year on bottle refunds.

- Recycling bottles into new bottles avoids using new raw materials to make the new bottles. There are less CO2 emissions and less water used to process them.

- There are few recycling containers for drinks consumed away from home. The implementation of a refund scheme would make it worthwhile for businesses like cafes and restaurants who sell a lot of these bottled drinks to collect the bottles and cash them in for the refund.

- There are a number of new jobs that are created to run and administer the scheme.

The Australian state of Victoria has submitted a bill to the State parliament to have such a scheme introduced for Victoria. There are approximately 2 billion plastic bottles consumed in the state a year. (4.4 billion containers in total, including glass, aluminium, and steel.) Only 28% are currently recycled. In this scheme the manufacturers would pay to the state EPA a fee of 10 cents for every drink container they produce. This cost can be passed on to the consumer if the manufacturer wishes to do so. The consumer gets the 10 cents back when they return the bottle. For all the bottles that still do not get returned (estimated to be approximately 20%), the funds already paid by the manufacturers on these bottles can then be used to operate and administer the fund and any excess funds returned to the state. This would generate an estimated $56 million per annum for the state. These funds are to be used to run the recycling depots, administration costs, promotion of recycling education, and infrastructure.

Why isn’t there a bottle refund scheme every where? The benefits are obvious with less litter and increased revenue for the organisers to fund further programs. Surely the bottle manufacturers would support it too as they pass on the cost and they get to see a clean environment without their product littered. However, it seems to be not the case. Manufacturers would rather fight such a scheme due to their costs and seem acceptable to seeing their products littering the environment, with little thought to what the rest of society would like.

Plastic Bags

|

What about the ubiquitous grocery store plastic bag? Where do we start? Plastic bags are popular with consumers and retailers as they are a convenient, lightweight, strong, cheap, and hygienic way to transport food and other products. However the bags contribute to greenhouse gases, clog up landfills, litter streets and streams, and kill wildlife.

Globally we use a trillion bags a year. That is approx 10 million every 5 minutes.

Fortunately there may be some good news on this issue. More and more businesses, organisations, municipalities and public offices are restricting, banning or enticing business to charge for plastic bags. In 2002 Ireland’s bag consumption dropped by 90% within a few months when a 15 cent Euro tax was imposed for the bags. IKEA in the USA saw a 92% drop in plastic bag usage after one year with only a 5 cent surcharge on their bags. IKEA Australia started charging 10 cents AUD per bag and saw a drop of 87% in 2002.

In 2002 Australia used 6 billion light weight plastic bags. The introduction of reusable plastic bags and the increasing awareness of the environmental issues of plastic bags dropped their use down to 3.9 billion in 2007. 2.96 billion of these came from supermarkets, while the others were used by fast food restaurants, service stations, convenience stores, liquor stores and other shops. In 2008 consumption then rose to 4.84 billion!

Most of these go to landfill after they are used although some are recycled (only 14%). In 2002 around 50 to 80 million bags ended up as litter in our environment. While the number littered has probably been reduced since then, it is likely that a large number still enter the environment. Once they are littered, plastic bags find their way on to our streets, parks, and finally into our waterways.

| Bag in Ocean | Bag in Air | Bag on Beach | Bag in Trees |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

It takes only four grocery shopping trips for an average Australian family to accumulate 60 plastic shopping bags.Nearly half a million plastic bags are collected on Clean Up Australia Day each year. Although plastic bags make up only a small percentage of all litter, the impact of these bags is nevertheless significant. Plastic bags create visual pollution problems and can have harmful effects on aquatic and terrestrial animals. Plastic bags are particularly noticeable components of the litter stream due to their size and can take a long time to fully break down.

- Plastic bags are produced from polymers derived from petroleum. The amount of petroleum used to make a plastic bag would drive a car about 11 metres. (12 yards)

- In 2005, Australians used 192 HDPE bags per capita.

- Over 35,000 bags are dumped to Australian landfills every 5 minutes.

In 2009 South Australia led the nation with a ban on lightweight, checkout-style plastic bags. Research undertaken by the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science at the University of SA showed that more than nine in ten shoppers took reusable bags to do their shopping, compared to about six in ten before the ban took effect.

In Australia’s Northern Territory, from 1 September 2011 Territory retailers can no longer supply lightweight, “checkout” style plastic bags, including degradable bags.

In the USA, there are 102 Billion bags used per year, or approximately 1 million per 5 minutes.

The presence of well funded and powerful lobbying groups such as the American Chemical Association in the USA has led to a number of unsuccessful attempts to ban or tax plastic bags. They argue that in-store recycling makes more sense than a ban. In reality, only 1 to 2% of plastic bags end up getting recycled.

Oregon plastic bag ban dead 10 June 2011

Plastic Bag Ban Fails in California Legislature, 1 Sept 2010

Seattle Rejects Its Plastic Bag Tax, 19 Aug 2009

Colorado. lawmakers bag statewide plastic bag ban, 25 Feb 2009

Michigan, USA –a bill to phase out all disposable plastic bans by 2012 died, 2008

Detroit MI, USA – ripped apart by Mayoral scandals and unemployment, plastic bags aren’t even on the map … although they are all over the streets

Missouri, USA –Senate bill 340 to ban died in committee 2009

Unfortunately the list goes on.

However the presence of a list shows that the topic is a contentious one and the issues associated with plastic bags are getting more and more attention. There have been a number of successes in other cities and support for increasing bans or taxes to reduce plastic bag usage is increasing.

“This issue is not going away,” says Ronald Fong,. CEO of the California Grocers Association, an industry group that backed California’s proposed ban. “The future is in reusable bags.”

San Francisco has calculated that plastic Bags cost them 17 cents to handle each discarded bag. Over the state, California spends about 25 million dollars sending plastic bags to landfill each year, and another 8.5 million dollars to remove littered bags from streets. While a grocery store owner pays next to nothing for plastic bags and gives them to customers at no charge, the follow on costs to the rest of us is much higher.

Plastic Waste and Wildlife

Entanglement and ingestion are the two primary kinds of direct damage to wildlife caused by marine litter.

Plastic shopping bags have a surprisingly significant environmental impact for something so seemingly innocuous. As well as being an eyesore, plastic shopping bags kill large numbers of wildlife each year. (Next time you are outside, have a look around. You’ll be

|

amazed at the number of plastic bags littering our streets and waterways.) In the water, plastic bags can be mistaken for jellyfish by wildlife. This makes plastic bag pollution in marine environments particularly dangerous, as birds, whales, seals and turtles ingest the bags then die from intestinal blockages. Disturbingly, it is claimed that plastic bags are the most common man-made item seen by sailors at sea.

One of the biggest problem with plastic bags is that they do not readily break down in the environment, with estimates that it takes from twenty to thousands of years for them to decompose. One of the disquieting facts stemming from this is that plastic bags can become serial killers. Once an animal that had ingested a plastic bag dies, it decays at a much faster rate than the bag. Once the animal has decomposed, the bag is released back into the environment more or less intact, ready to be eaten by another misguided organism. The incredibly slow rate of decay of plastic bags also means that each bag we use compounds the problem, because the bags simply accumulate.

Plastic bags are often mistakenly ingested by animals, clogging their intestines which results in death by starvation. Other animals or birds become entangled in plastic bags and drown or can’t fly as a result.

Even when they photo-degrade in landfill, the plastic from single-use bags never goes away, and toxic particles can enter the food chain when they are ingested by unsuspecting animals.

Greenpeace report that at least 267 marine species are known to have suffered from getting entangled in or ingesting marine debris. Nearly 90% of that debris is plastic.

Of 115 species of marine mammals, 49 species are known to become entangled in and/or ingest marine litter. Seals and sea lions are curious by nature and have a tendency to investigate new things, sometimes with fatal results. Whales, dolphins, and porpoises have been found entangled in fishing nets and line. Manatees have become entangled in crab-pot lines. Elephant seals, sea lions, manatees, pygmy whales, sperm whales and round toothed dolphins have all been found dead from suffocation or starvation after having ingested marine litter such as plastic bags and plastic sheeting. Sea turtles also become entangled in fishing line, rope and nets, yet ingestion is an even larger problem. They eat plastic bags because the bags look like jellyfish, their favourite food. The bags cause the turtle’s digestive tracts to become blocked, leading to starvation. About 100,000 marine mammals, including some 30,000 seals and large numbers of turtles, are killed by plastic marine litter every year around the world.

|

Sea birds are also frequent victims of abandoned or lost fishing nets. Because most sea birds feed on fish, they are often attracted to fish caught or entangled in discarded nets or fishing lines. Many birds including ducks, geese, cormorants and gulls are also entangled in six pack rings and other encircling pieces of marine litter. Of the worlds’ 312 species of seabird, 111 species are known to ingest plastics. Between 700,000 and one million seabirds are killed from entanglement or ingestion each year.

Fish and crustaceans (lobsters, crabs) are frequently caught in lost or discarded fishing gear as well. Corals are damaged when discarded fishing gear and nets draw along the ocean floor or through the reefs. When the reefs are destroyed, it affects other animals that are dependent on that environment.

In our oceans, some of the long-lasting plastics end up in the stomachs of marine birds and animals and their young. . Besides the particles’ danger to wildlife, the floating debris can absorb organic pollutants from seawater, including PCBs, DDT, and PAHs. Aside from toxic effects, when ingested, some of these are mistaken by the endocrine system as estradiol, causing hormone disruption in the affected animal. These toxin-containing plastic pieces are also eaten by jellyfish, which are then eaten by larger fish. Many of these fish are then consumed by humans, resulting in their ingestion of toxic chemicals. Marine plastics also facilitate the spread of invasive species that attach to floating plastic in one region and drift long distances to colonize other ecosystems.

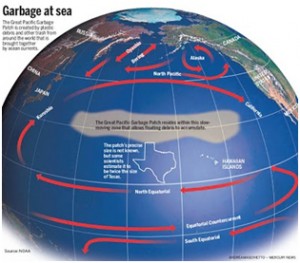

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch

A concentration of debris floating in the Pacific, that’s twice the size of Texas, according to marine biologists. The enormous stew of trash – which consists of 80 percent plastics and weighs some 3.5 million tons, say oceanographers – floats where few people ever travel, in a no-man’s land between San Francisco and Hawaii.

It is located in the North Pacific Gyre, which is a body of rotating current driven by a repeating wind pattern. In 1999, its plastic abundance was estimated at 335,000 items km2 and 5.1 kg/km2, roughly an order of magnitude greater than samples collected in the 1980s showing how fast this plastic waste is accumulating. The United Nations in 2006 estimated that each square km of regular ocean carries 18,000 (46,000 per square mile) pieces of debris but added caution that this number has not been accredited to a particular source. They reported that 10% of the plastic produced every year worldwide winds up in the ocean. 70% of which finds its way to the ocean floor, where it will likely never degrade.

|

In 2001 researchers found in many of the sampled areas, the overall concentration of plastics was seven times greater than the concentration of zooplankton.

The discovery is attributed to Captain Charles Moore who sailed through the Gyre, taking a short cut on his way home from a sailing race in his boat called Alguita. He reports “I often struggle to find words that will communicate the vastness of the Pacific Ocean to people who have never been to sea. Day after day, Alguita was the only vehicle on a highway without landmarks, stretching from horizon to horizon. Yet as I gazed from the deck at the surface of what ought to have been a pristine ocean, I was confronted, as far as the eye could see, with the sight of plastic.

It seemed unbelievable, but I never found a clear spot. In the week it took to cross the subtropical high, no matter what time of day I looked, plastic debris was floating everywhere: bottles, bottle caps, wrappers, fragments. Months later, after I discussed what I had seen with the oceanographer Curtis Ebbesmeyer, perhaps the world’s leading expert on flotsam, he began referring to the area as the “eastern garbage patch.”

Marcus Eriksen, director of research and education at the Algalita Marine Research Foundation in Long Beach, said his group has been monitoring the Garbage Patch for 10 years. “With the winds blowing in and the currents in the gyre going circular, it’s the perfect environment for trapping,” Eriksen said. “There’s nothing we can do about it now, except do no more harm.” The patch has been growing, along with ocean debris worldwide, tenfold every decade since the 1950s, said Chris Parry, public education program manager with the California Coastal Commission in San Francisco.

Ocean current patterns may keep the flotsam stashed in a part of the world few will ever see, but the majority of its content is generated onshore, according to a report from Greenpeace last year titled “Plastic Debris in the World’s Oceans.” The report found that 80 percent of the oceans’ litter originated on land. While ships drop the occasional load of shoes or hockey gloves into the waters (sometimes on purpose and illegally), the vast majority of sea garbage begins its journey as onshore trash. That’s what makes a potentially toxic swamp like the Garbage Patch entirely preventable, Parry said. “At this point, cleaning it up isn’t an option, it’s just going to get bigger as our reliance on plastics continues. … The long-term solution is to stop producing as much plastic products at home and change our consumption habits.”

In January 2008, Moore, Eriksen and other researchers boarded a 25-ton, aluminum-hull catamaran for a month long trip to the gyre. The concentration of debris increased to 0.01 grams of plastic in each square metre of water from 0.002 grams in 1999, Eriksen said.

“Every product now is expected to be wrapped in plastic, and there is no take-back infrastructure for that packaging,” Moore said. “This lubricant of globalization has no end game. There’s no after-life for it and since the ocean is downhill from everywhere, that’s where it ends up.”

About 600 tons of industrial fishing gear washed up on North-western Hawaiian Islands in the past decade, threatening the Hawaiian monk seal, the most endangered U.S. marine mammal, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

|

Climate change and marine debris are the most serious threats to the islands’ ocean habitats, said Rusty Brainard, head of coral reef ecosystem research at the NOAA. “All the plastic is unbelievable,” said Brainard, 49. “These are places that are uninhabited, thousands of miles from where anybody lives, and yet they are just covered in human trash.”

Wildlife eating plastic from the Pacific Gyre.

At right, photograph from the Midway Islands, near the heart of the Pacific Trash Gyre , showing the decomposed bodies of chicks that have been fed plastic litter by confused parents.

|

According to the Washington-based American Chemistry Council, an industry trade group. “There is no correlation between plastic production and marine debris”, said Sharon Kneiss, vice president of the organization.

“Plastics don’t belong in the ocean; they don’t belong in the roadway; they belong in the recycling bin,” Kneiss said. “Yes, there are plastics and other debris in the gyre. It is a problem that we’re concerned about.”

Plastic (Resin) Pellets Spillage

|

Plastic (resin) pellets are the raw material pellets shipped around the world to manufacturers to use to make their final plastic products. Inappropriate packaging for the dangerous product they are, their transport and handling issues are a major problem. Mishaps can easily happen, resulting in millions of beads being released into the environment.

The potential scope of the problem is staggering. Every year approximately 5.5 quadrillion (5.5 x 1015) plastic pellets—about 250 billion pounds of them—are produced worldwide for use in the manufacture of plastic products. When those pellets or products degrade, break into fragments and disperse, the pieces may also become concentrators and transporters of toxic chemicals in the marine environment. Thus an astronomical number of vectors for some of the most toxic pollutants known are being released into an ecosystem dominated by the most efficient natural vacuum cleaners nature ever invented: the jellies and salps living in the ocean. After these organisms ingest the toxins, they are eaten in turn

|

by fish, and so the poisons pass into the food web that leads, in some cases, to human beings. Farmers can grow pesticide-free organic produce, but can nature still produce a pollutant-free organic fish?

Hideshige Takada, an environmental geochemist at Tokyo University, and his colleagues have discovered that floating plastic fragments accumulate hydrophobic-that is, non-water-soluble-toxic chemicals. Plastic polymers, it turns out, are sponges for DDT, PCBs, and other oily pollutants. The Japanese investigators found that plastic resin pellets concentrate such poisons to levels as high as a million times their concentrations in the water as free-floating substances.

|

Pellets constitute about 70% of plastics eaten by seabirds. Eagles and other predators high in the

food web have been found to contain large concentrations of pellets in their stomachs after preying on smaller birds. In that way toxic substances will bioaccumulate.

Mr. Smith of Tangaroa Blue Ocean Care Society in Australia said “we are now beginning to get an idea of the scale of marine plastic pollution and how extensive micro-pollutants such as plastic resin pellets are.” These pellets can be found in the thousands, and sometimes millions, on a single Western Australia beach. The pellets are often difficult to detect due to their size and colour against the sand and could take lifetimes to sift out of the continually varying seashore.

|