Where are we headed for Waste Plastic Management? – Australia

Posted on August 30, 2021 by DrRossH in Plastic Limiting RegulationsWe have gotten very good at manufacturing with plastic these past few decades, but we are struggling how to dispose of it. Considerable confusion exists with how this is to happen, what the terms like recycling really mean for a plastic, and who is responsible for paying for this.

In 2025, the Federal government is introducing a National Plastics Target1 for companies to follow in Australia around their plastic use and the waste disposal problem that it is making. The new targets include,

- 100% reusable, recyclable or compostable packaging.

- 70% of plastic packaging being recycled or composted.

- 20% of average recycled content included in packaging.

Since the start of 2021, a lot of attention has been given to these goals by government, industry, media, consulting and legal companies. This has made a lot of confusion on what all the terms mean and how it is sometimes difficult for people and organisations to unpack and make sense of these terms in digestible and relatable scenarios

Can Plastic be Recycled? When we think of recycling, we think of an item like a metal can that can be used, sent back for recycling then remelted down and made into a new can or other metal item without losing any of the metal’s desirable properties. Unlike a metal, plastic has a molecular structure. The properties of the plastic material are based on that molecular structure being intact. It can only be mechanically recycled 2-3 times before that structure is so damaged that it needs to be disposed of or blended with virgin plastic. Therefore, often all recycling is doing is delaying the inevitable of disposal and for single use items, this could be a delay of 1-2 years only. We should not believe we can quickly go down a path that will solve all our plastic problems if we recycle it all. This has been tried many times in the past and it has failed every time2. We have more waste plastic now than ever before in spite of all previous good intentions.

Plastic is generally down cycled not recycled. Down cycled is used to produce less technical more simple uses like clothes, furniture, or roads. Putting plastic waste into road making is not recycling. This is more of a onetime reuse of the waste material and it is never to be used again. If recyclable plastic is to be recycled in a circular economy, then using it in roads is not what we ought to be doing. That is more suited to non recyclable plastic waste.

What is Reusable? The term reusable is commonly associated with reusing the product for another purpose or by another person. For example, using an empty plastic ice cream container to store food. However, in many of the applications being branded as recycling at the moment, they are more of a material reuse. In material reuse, the plastic product is reprocessed into another one-time application after which the material is no longer suitable for any other use. For example, putting plastic waste in roads as mentioned above. In these applications the plastic material is not part of the circular recycling economy. Many of the recycling mentions in the media these days really fall into the category of material reuse. It is important to make this distinction as in a circular economy not much in the way of virgin materials would need to be introduced. In a material reuse economy, there will still be considerable virgin materials required to replace the products lost from the recycling loop.

It will be expensive to set up infrastructure to return the plastic waste back from the millions of end users. It must be collected and shipped to processing plants. State governments have recently experienced this during their set up container deposit schemes. In this scheme, the end users will receive some compensation to return their empty drink containers to a collection point. Until those schemes are in place, most people dispose of their containers in the rubbish or as litter. Once at a reprocessing plant, plastic waste needs to be sorted into the various plastic types, and the various colours. Then each type can be appropriately processed. There is very little infrastructure in place to do this at the moment and it will take a long time to set this up and incentivize users to use it. Only 4.3% of plastic is currently recycled in Australia3. Plastic that goes to landfill is not biodegradable so it will still last hundreds of years buried in the ground.

Australia is a smallish economy which limits the size of its industry types. What maybe recyclable in a large overseas economy will not necessarily be recyclable here. In the government target, it does not clarify, does recyclable mean recyclable in Australia or somewhere else? The targets mentioned are just targets, not actual requirements. What will happen to the plastic waste from companies who will not follow the targets?

Compostable Plastics, Sounds Good?

Compostable plastics are made from plant materials so have a very different molecular structure than fossil fuel-based plastics. They are not recyclable therefore with other plastics. This means they are to be disposed of after their use. Reuse may be possible, but the compostable plastics are lower strength, have a limited lifetime before they deteriorate and will therefore fail sooner. This precludes them from any circular economy discussions. They are a linear economy, Make-Take-Waste just like we have done for the last 70 years with conventional plastic. This constant manufacturing of disposable items also contributes to high energy use and climate change.

Currently only a fraction of plastics produced today are plant based. If this were to be increased to be a significant portion of the world’s 380 million tons of plastic per year4 then where is the plant feed stock going to come? This would require significant use of arable land.

The term compostable is often spread over product labels, with the purpose to entice users they are using a more sustainable product. However, there are two grades of compostable plastic. Commercial compostable and Home Compostable. Commercial compostable is not so consumer friendly as it has to be disposed to a special facility for it to biodegrade. There are few such facilities around and those there are, are a long way from population centers. There is no infrastructure to collect commercial compost plastic, nor is there a required marking on the product to let consumers know has to go to commercial facilities. If a commercial compostable plastic is put in a rubbish bin and that goes to a landfill, it is too cool there for the necessary microbes to biodegrade it away.

Home compostable is more friendly to the user as it can be disposed of in a rubbish bin or a home compost bin. It will biodegrade way relatively quick in either location. Users do not need to go out of their way to dispose of it.

There are no standard symbols required to show products are made of Home compost or commercial compost materials. So end users cannot tell them apart and do not know how to dispose of them. The ‘if in doubt’ the ‘throw it out’ philosophy applies more often.

Home compostable is plant based, but in reality, it is still more than 50% fossil fuel based with the PBAT material to allow it to biodegrade at low ambient temperatures.

Overall, compostable plastic while having some desirable attributes, has some big short comings as well and cannot offer what the targets would have us believe.

70% of plastic packaging being recycled or composted.

When we look at this target, it is difficult to see how we can get from 4.3% recycled to 70% in 3 years when we have struggled to get to 4.3% in the last decade. As mentioned above, this requires getting plastic waste back from millions of users and being reprocessed and while remaining competitive to imported virgin plastic. This is an enormous task and if history is to show us, then it says we are highly unlikely to get there. A recent comment from the Waste Management and Resource Recovery (WMRR) Association of Australia, stated5 that “as with any new initiative of this size, there are bound to be teething issues, many of which relate to the complexity of what we are addressing and the long timeframes required to set up waste and resource recovery facilities – from the planning approval stage, to receiving specialist equipment from overseas, to construction and commissioning”.

WMRR also report6, In looking to Europe, we must also acknowledge that while the ambitious federal and state resource recovery targets are supported, evidence from numerous EU members (and other countries) that have established decades-long WARR systems (that Australia does not have) show that consistently hitting the 70% target has not been achieved to-date.

The imposition of a virgin plastics tax as some countries7 are discussing would be one mechanism that would push industry to be actively involved in this. That word tax has become such a political word these days, many governments however, would not be willing to look at this option. A statement by the Ellen MacArthur foundation8 on using Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) as a means to generate funds to drive the needed change. However, for many years to come, mechanisms that ensure dedicated, ongoing, and sufficient funding will be necessary to cover that net cost. Without such funding mechanisms, it is unlikely that packaging collection and recycling will scale to the extent required, and tens of millions of tonnes of packaging will continue to end up in the environment every year.

Compostable packaging will need to be correctly disposed of after use. If it is not disposed to the correct place, it will not biodegrade way.

If we currently recycle 4.3% of plastics, then where would all this extra recycled packaging being returned, be used? Australia does not have enough manufacturing industry and consumer demand to use it all. Not all plastic is made from clear material, hence it begs the question what are coloured plastics pulled out of the recycle stream, going to be used for? In addition, a lot of plastics are custom made for their original application. Additives such as flexibilisers, uv protectors, are used that give the initial product it’s materials properties. These may not suit another product. How will they be separated out and treated is another complex question.

The national plastics plan still has an allowance for plastic to be ‘recycled’ as being sent offshore to other countries. Either as clean feed stock or as fuel for thermal processes such as cement kilns. The regulations first read as being tight on this, but a lot of the compliance seem to be self-issued compliance. Again, when we look at history, there are numerous cases of operators rorting the system to avoid compliance costs. Will this be any different this time is the question?

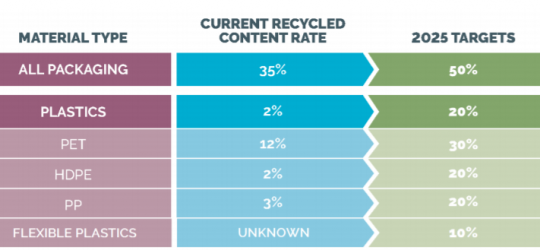

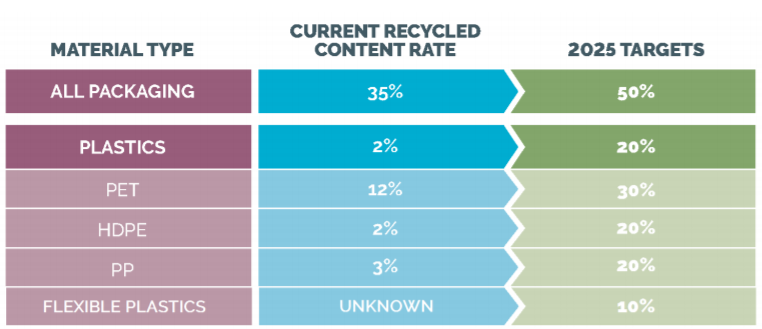

20% of average recycled content included in packaging.

This is actually an aggregate of several different rates for different materials9.

When a review of the above chart is made, it shows overall plastic recycled content is to increase by 10 times. This will require a substantial change in manufacturing operations. Sourcing high quality feed stock at competitive costs will be difficult. Otherwise those companies that do not follow the targets will have a economic advantage which is the opposite of what this plastic reform is aiming to achieve.

Consider too what 20% recycled content means. Take for example, a typical HDPE product like a milk bottle. To incorporate the recycled content of one used bottle means that virgin material for four other bottles needs to be used.

For soft of flexible plastics, they are harder to recycle. Their target recycled content is only 10%. For one plastic bag to be recycled requires virgin material for 9 other plastic bags to be used.

The above two examples show us that low targets like these are not going to have significant impact on soling the plastic waste issues the world has now.

Australia imports a lot of packaged items. How is a small economy like Australia to mandate this on imported packaging? It is more than likely is not possible. Therefore, this target would only apply to domestic manufactured packaging materials. The percent of packaging material made in Australia compared to imported would be small. While encouraging Australian manufacturers to include recycled content in their products is a great outcome, the impact on the overall situation is likely to be even less.

The cost to manufacturers to change over their production lines to sourcing, using recycled content and guaranteeing the finished products properties will not be small. To achieve this in three years, many will require substantial support. Another consideration that is not openly discussed which could potentially have costly ramifications is, who is going to be responsible for the purity and integrity of the packaging? If there was a food contamination issue or if the recycled packaging fails somehow and the product spoils, then who is responsible? It is the plastic manufacturer, the recycled content supplier, or the government for imposing these requirements? There are many potential legal issues here.

There is no doubt that we need to address the issue of plastic consumption and how to properly dispose of it. For many years this has not been addressed in Australia despite overwhelming evidence to say plastic waste reform has been needed. 2025 will introduce some new goals for industry which will be very welcome. They will cause some changes to be made, some companies will change their processes, new infrastructure will be set up and some behaviors will change. However, without a mandate, ratcheting up of the targets, and considerable support we will more than likely be having the same discussion when 2025 has long passed down the road.

How many people today grab a takeaway coffee cup from the local cafe to drink on the go? We don’t know, but the number must be enormous.. Most every one of the above have a plastic top that will last 100s of years. Some cafes still use plastic cups that last a similar time. Is 10 minutes of coffee worth 100s of years of trash?

These items can be seen littering our gutters and on our streets all over the place. If they were all cardboard, they would still be littered, but they would, at least, be gone in a short time.

They do not need to be made of plastic.

How many people today grab a takeaway coffee cup from the local cafe to drink on the go? We don’t know, but the number must be enormous.. Most every one of the above have a plastic top that will last 100s of years. Some cafes still use plastic cups that last a similar time. Is 10 minutes of coffee worth 100s of years of trash?

These items can be seen littering our gutters and on our streets all over the place. If they were all cardboard, they would still be littered, but they would, at least, be gone in a short time.

They do not need to be made of plastic.

On the way home from the gym last week, a distance of about 1 km (1/2 mile), I counted the items of plastic litter on the curb as I walked. In that short distance I counted 63 pieces of plastic litter. Plastic drink bottles, bottle tops, candy wrappers, plastic film, polystyrene fragments etc. That seemed to be a lot to me. I guess it is a generational thing. Our parents would have been horrified to see that amount, whereas it seems to go unnoticed by our youth of today. In another 20 years how many pieces will there be on this stretch, -- 200? What will today’s youth think of that new amount then when they are older? Will their children be so readily accepting of a higher amount of litter?

On the way home from the gym last week, a distance of about 1 km (1/2 mile), I counted the items of plastic litter on the curb as I walked. In that short distance I counted 63 pieces of plastic litter. Plastic drink bottles, bottle tops, candy wrappers, plastic film, polystyrene fragments etc. That seemed to be a lot to me. I guess it is a generational thing. Our parents would have been horrified to see that amount, whereas it seems to go unnoticed by our youth of today. In another 20 years how many pieces will there be on this stretch, -- 200? What will today’s youth think of that new amount then when they are older? Will their children be so readily accepting of a higher amount of litter?

Discussion · No Comments

There are no responses to "Where are we headed for Waste Plastic Management? – Australia". Comments are closed for this post.Oops! Sorry, comments are closed at this time. Please try again later.